About Me CV Research GitHub Google Scholar

Success Weighted By Completion Time: A Dynamics-Aware Evaluation Criteria for Embodied Navigation

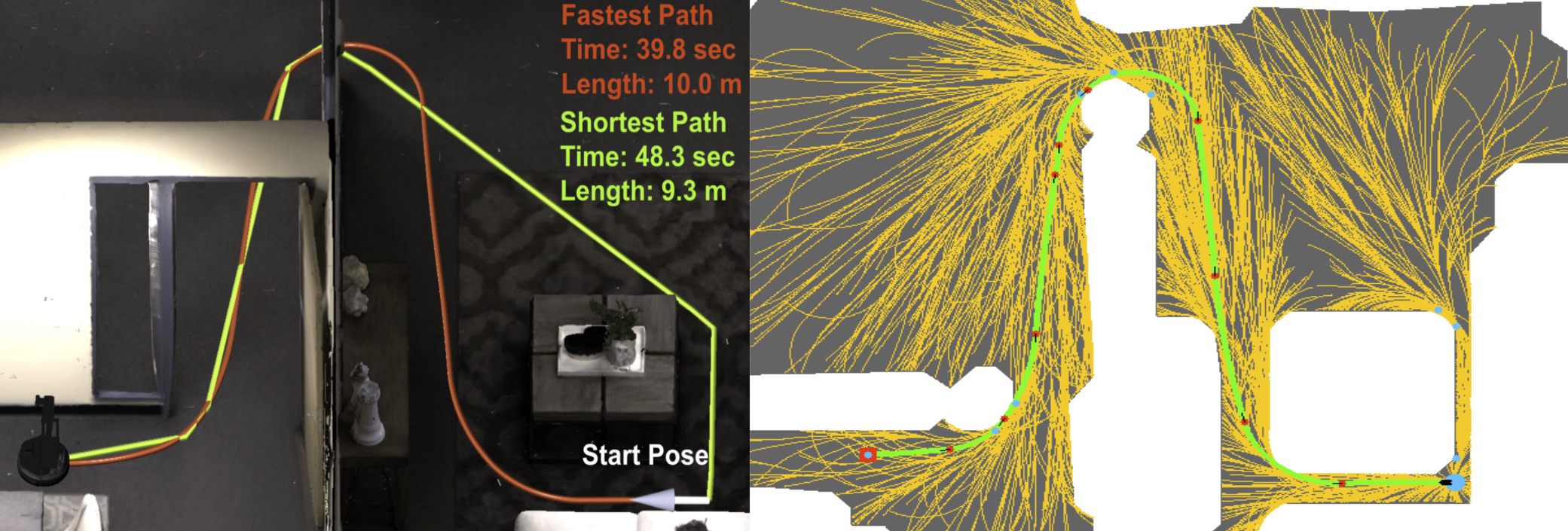

The shortest path is not always fastest, depending on the agent's dynamics (left). RRT*-Unicycle explicitly considers the agent's dynamics to measure how well its learned behavior approximates the fastest possible one (right)

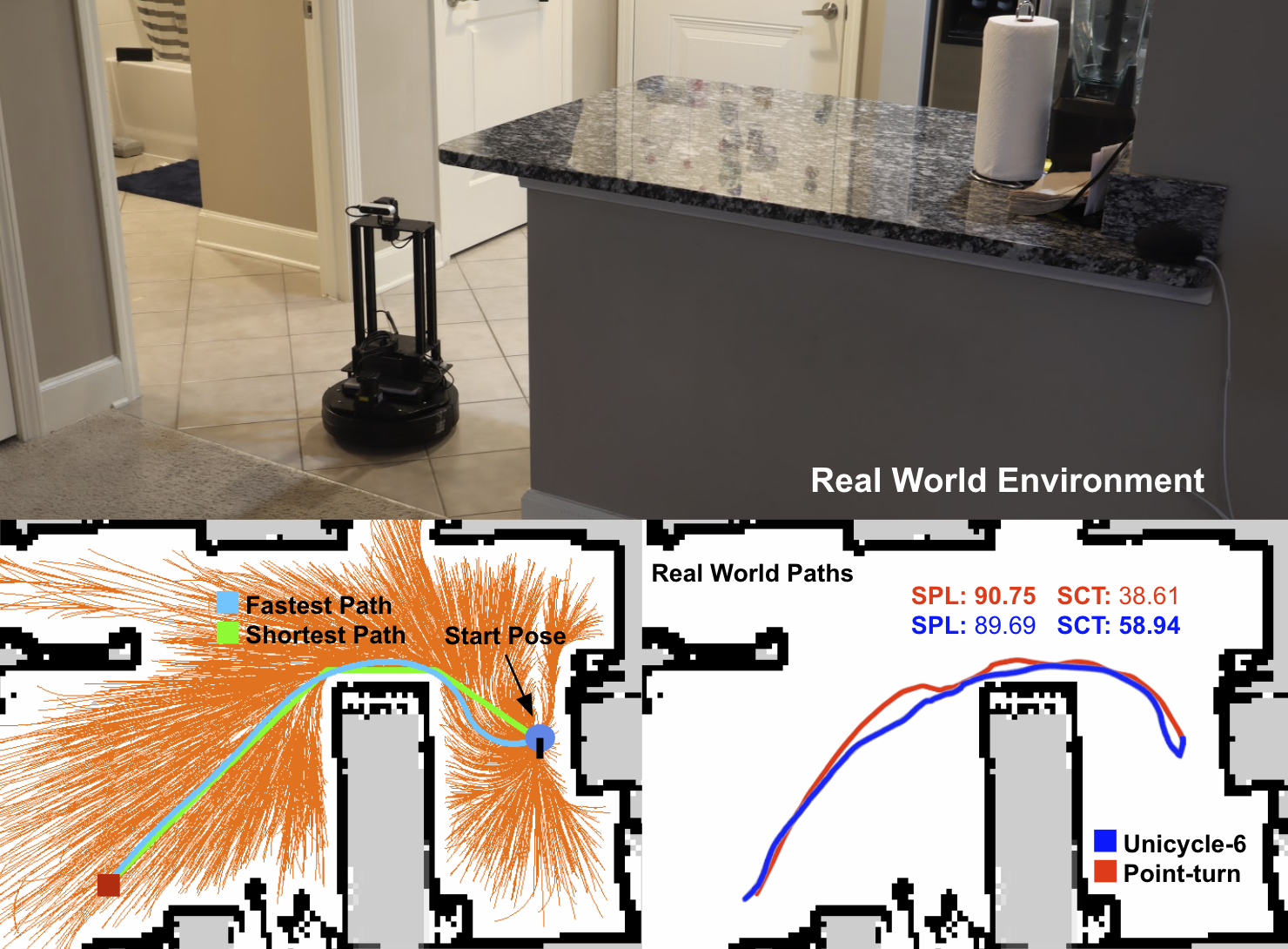

Our trained agents could successfully navigate to the goal position faster than agents modeled after previous works when deployed on a real robot in an apartment

We present Success weighted by Completion Time (SCT), a new metric for evaluating navigation performance for mobile robots. Several related works on navigation have used Success weighted by Path Length (SPL) as the primary method of evaluating the path an agent makes to a goal location, but SPL is limited in its ability to properly evaluate agents with complex dynamics. In contrast, SCT explicitly takes the agent's dynamics model into consideration, and aims to accurately capture how well the agent has approximated the fastest navigation behavior afforded by its dynamics. While several embodied navigation works use point-turn dynamics, we focus on unicycle-cart dynamics for our agent, which better exemplifies the dynamics model of popular mobile robotics platforms (e.g., LoCoBot, TurtleBot, Fetch, etc.). We also present RRT*-Unicycle, an algorithm for unicycle dynamics that estimates the fastest collision-free path and completion time from a starting pose to a goal location in an environment containing obstacles. We experiment with deep reinforcement learning and reward shaping to train and compare the navigation performance of agents with different dynamics models. In evaluating these agents, we show that in contrast to SPL, SCT is able to capture the advantages in navigation speed a unicycle model has over a simpler point-turn model of dynamics. Lastly, we show that we can successfully deploy our trained models and algorithms outside of simulation in the real world. We embody our agents in a real robot to navigate an apartment, and show that they can generalize in a zero-shot manner. A video summary is available here: https://youtu.be/QOQ56XVIYVE

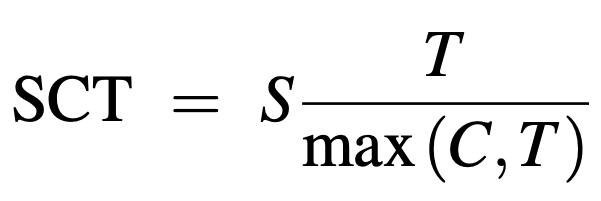

Success weighted by Completion Time

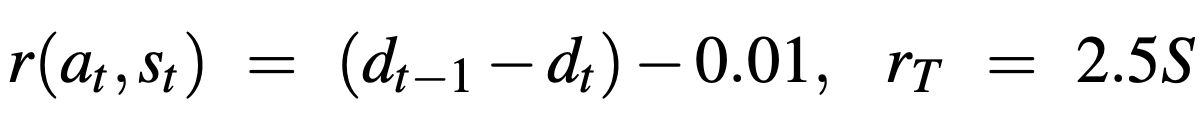

To overcome all of these limitations of SPL, we propose Success weighted by Completion Time (SCT), as defined above, where C is the agent's completion time, and T is the shortest possible amount of time it takes to reach the goal point from the start point while circumventing obstacles based on the agent's dynamics. One alternative to SCT we considered was simply computing the agent's average completion time on successful episodes. However, computing the lower and upper bounds of the average completion time is not trivial, making it difficult to tell how well the robot could have performed the task. It is also not comparable across datasets; for example, if one dataset contains navigation environments larger than another dataset's on average, its average successful completion time would likely be longer in comparison. SCT addresses these issues by measuring how close an agent's completion speed is to being optimal, using pre-computed fastest paths to compare the agent's paths against.

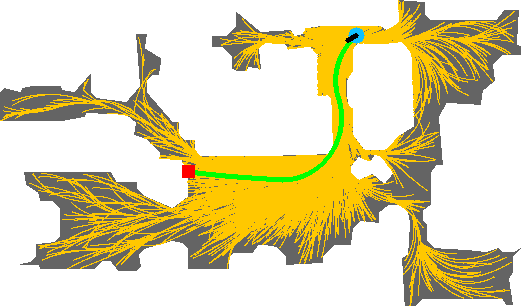

Calculating the fastest path time: RRT*-Unicycle

A tree created with RRT*-Unicycle for calculating the fastest path. Fastest found paths to all sampled points shown in yellow, and fastest found path to the goal in green. These paths consider the maximum linear and angular velocities of our unicycle-cart agents, as well as its initial heading at the start of the episode. Neither the maps nor the paths are provided to the agents during training or testing; they are for performance evaluation purposes only.

To compute SCT, we need to compute the fastest possible completion time of an episode. Although a navigation mesh, an auxiliary data structure often provided by simulators representing the navigable areas of an environment, greatly simplifies the process of finding shortest paths using A*, they do not encode anything about a given agent's dynamics. Therefore, it cannot be easily exploited to find the fastest path. For such a task, creating a new graph using RRT* that considers the agent's dynamics is often the preferred approach. We develop an adapted version of RRT*, which we call RRT*-Unicycle, to find the fastest path from the start to the goal of an episode that is conditioned on the robot's dynamics. Recall that RRT* is a sampling-based optimal motion-planning algorithm that, given a map, finds an obstacle-free path between two points that minimizes a cost, and is known to approach the optimal solution as the number of samples approaches infinity. The cost we aim to minimize is the time it takes the agent to travel from its starting pose to the goal point. RRT* works by creating a graph that traverses the free space of an environment, constructing and optimizing collision-free paths between sampled points until a full path from the start to the goal can be assembled.

Reward schemes

We consider two reward schemes, the shaped reward scheme used by Wijmans et al., as shown below:

as well as a decaying reward scheme as shown below:

where dt is the distance from the goal at time t, S is 0 or 1 depending on whether the agents successfully reached the goal or not, and β decays to 0 as training progresses. The goal of the decaying reward scheme is to eventually provide the agent with only a negative constant step reward and a large positive constant terminal reward; the latter encourages the agent to complete the episode successfully, while the former encourages it to do it as quickly as possible. We do not immediately remove the geodesic portion of the reward at the start of training because the reward may be too sparse to learn optimal behaviors. Specifically, an agent early in training that has likely not learned to consistently reach the goal yet would be encouraged to simply terminate the episode immediately, such that it can avoid accruing the negative step reward. The geodesic term provides the positive reward signal necessary, even during the early stages of training, to lead the agent to the goal and teach it about the existence of a large positive terminal reward. Once the agent has learned that continuing the episode can lead to a large reward, we find that it continues to do so even as the geodesic term is completely eliminated.

Results

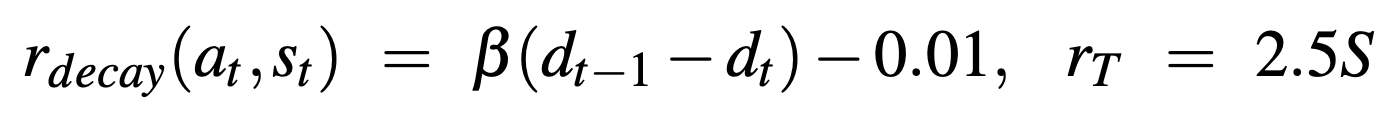

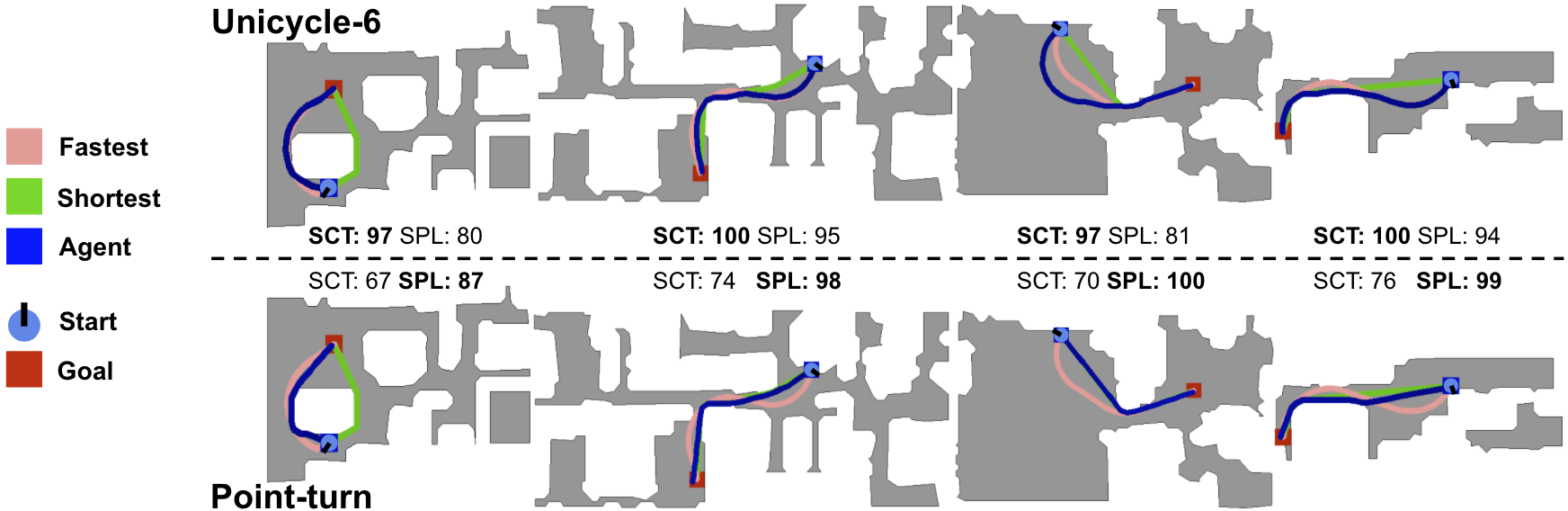

The unicycle agents learn to leverage their dynamics to complete episodes faster than point-turn agents (higher SCT) by using smoother turns, which leads to longer paths and consequently lower SPL.

Example episodes completed in a real apartment:

Citation:

@inproceedings{sct21iros,

title = {Success Weighted by Completion Time: A Dynamics-Aware Evaluation Criteria for Embodied Navigation},

author = {Naoki Yokoyama and Sehoon Ha and Dhruv Batra},

booktitle = {2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS)},

year = {2021}

}